Is quality of life associated with cognitive impairment in schizophrenia?

Is quality of life associated with cognitive impairment in schizophrenia?

Köksal Alptekin, Yıldız Akvardar,Berna Binnur Kivircik Akdede*, Kemal Dumlu, Doğan Işık, Ferdane Pirinçci, Saida Yahssin, Arzu Kitiş

Psychiatry Department, Medical School of Dokuz Eylul University, Balçova, 35340, Izmir, Turkey

Accepted 19 November 2004

Available online 23 December 2004

Abstract

Background: The subjectively assessed quality of life of schizophrenia patients is mostly lower than healthy subjects, and cognitive impairment is an integral feature of schizophrenia. The aims of the present study were to compare the quality of life and neurocognitive functioning between the patients with schizophrenia and the healthy subjects, and to examine the relationships between quality of life and neurocognitive functions among the patients with schizophrenia.

Methods: Thirty-eight patients with schizophrenia (15 women and 23 men) and 31 healthy individuals (18 women and 13 men) were included in the study. All participants were administered World Health Organization Quality of Life–Brief Form (WHOQOL-BREF) to assess their quality of life, and Digit Span Test (DST) and Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT) for cognitive functions.

Results: The patients with schizophrenia demonstrated lower scores in physical (F=25.6, p=0.0001), psychological (F=15.85, p=0.0001) and social (F=37.7, p=0.0001) domains compared to control group. The patients with schizophrenia showed significantly lower scores on COWAT compared to healthy subjects (F=4.22, p=0.04). The social domain scores of WHOQOL correlated to DST total scores (r=0.45, p=0.007), DST forwards scores (r=0.54, p=0.001) and COWAT total scores (r=0.40, p=0.04) in patients with schizophrenia but not in the control group. The patients with lower level of cognitive functioning had lower scores on social domain of WHOQOL-BREF (z=-2.01, p=0.04).

Conclusion: Our results confirm that the cognitive deficits in executive function and workingmemory appear to have direct impact on the patients' perceived quality of life especially in social domain which can either be a cause or a consequence of social isolation of patients with schizophrenia.

© 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Cognition; Quality of life; Schizophrenia

Abbreviations: COWAT, Controlled Oral Word Association Test; DST, Digit Span Test; ESRS, Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QoL, Quality of Life; WHOQOLBREF, World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Form.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: +90 232 4124158 fax: +90 232 2599723

* E-mail adress:[email protected] (B.B. Kivircik Akdede).

0278-5846/$ - see front matter © 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.11.006

1.Introduction

Psychopathology can affect most aspects of life, such as physical and psychological state, as well as social, occupational and economic status. Decreased Quality of Life (QoL) is often an important cause or consequence of psychopathology and needs to be included in a comprehensive treatment plan (American Psychiatric Association, 1994). In psychiatry, the QoL concept is frequently used as a part of a multidimensional assessment of outcome in the evaluation of treatment efficacy. The QoL measures are especially important when treating patients with chronic conditions, such as schizophrenia, which significantly impair their life (Saleem et al., 2002). Every aspect of everyday life is affected, including where they live and work, what activities they can perform and how they interact with other people. The subjectively assessed QoL of patients with schizophrenia living in the community is mostly lower than healthy subjects (Bengtsson-Tops and Hansson, 1999; Hermann et al., 2002).

It is well known that cognitive deficits are an integral feature of schizophrenia. Some studies have found widespread impairments in many domains of neurocognitive function, including executive function, attention, perceptual motor processing, vigilance, verbal learning and memory, verbal and spatial working memory and verbal fluency (Braff et al., 1991; Kenny and Meltzer, 1991; Saykin et al., 1994). However, in contrast to the studies reporting widespread cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia, some studies have provided more selective cognitive dysfunction in patients with schizophrenia (Saykin et al., 1991). Cognition has been increasingly regarded as a crucial outcome in the assessment of treatment efficacy in schizophrenia as the neurocognitive deficits have been reported to be predictive of social functioning, occupational functioning and level of independence within the community in schizophrenia (Green, 1996; Meltzer et al., 1996; Velligan and Miller, 1999) which all can be included in QoL.

The purpose of this cross-sectional study is twofold. First, we attempt to examine the neurocognitive functioning and the quality of life of patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy subjects. Second, we attempt to examine the relationships between neurocognitive functioning and self-reported health related quality of life.

2.Methods

2.1. Patient population and study design

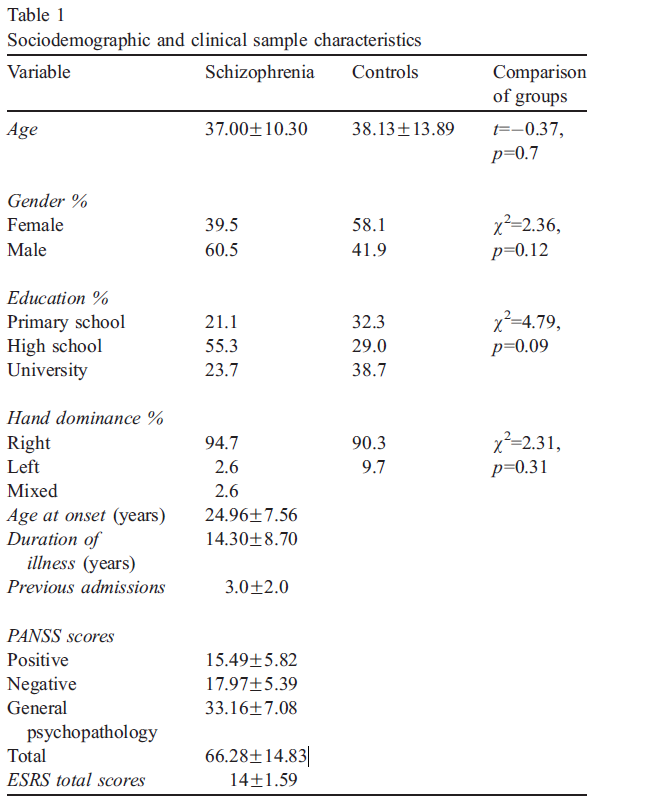

All subjects (15 women and 23 men) had a DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) who had been recruited from Psychiatry Department of Dokuz Eylul University in Izmir, Turkey. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) history of other concomitant Axis I disorder; (ii) past or present substance dependence/abuse; (iii) history of neurological disorder; and (iv) electroconvulsive therapy within the last 6 months. All patients were clinically stable on antipsychotics. Two patients were drug-free, 34 patients were on atypical antipsychotics and 2 patients were on typical antipsychotics. Thirty-one healthy individuals (18 women and 13 men) were included in the study as the control group. The study was described to each subject prior to obtaining written informed consent. There were not any significant differences between patient and control groups in age, gender and education (Table 1).

All subjects were evaluated by a structured diagnostic interview by the same psychiatrist. WHOQOL-BREF was given to the subjects after giving a detailed introduction. The neuropsychological tests and rating scales for psychopathology and extrapyramidal side effects were administered on the same day by a trained investigator.

2.2. Assessment instruments

2.2.1 World Health Organization Quality of Life–Brief Form

The subjective well-being was assessed by the Turkish version of WHO Quality of Life Measure–Abbreviated version (WHOQOL-BREF-TR). All the participants were administered WHOQOL-BREF to assess their quality of life. The WHOQOL is a generic quality of life instrument that was designed to be applicable to people living under different circumstances, conditions and cultures (WHOQOL Group, 1998a,b). The WHOQOL sets out to be a purely subjective evaluation, assessing perceived QoL, and in this way differs from many other instruments used to assess QoL (Orley et al., 1998). WHOQOL also accepts QoL as a multidimensional concept (Saxena and Orley, 1997). Two versions are available: (i) the full WHOQOL with 100 items and (ii) the WHOQOL-BREF with 26 items. WHOQOL-BREF, the generic profile instrument, useful in clinical and service evaluations was used in this study for reasons of brevity. It is suggested that the WHOQOL-BREF is sensitive to the health-related quality of life status of those with long-term mental illness (WHOQOL Group, 1998b; O’Carroll et al., 2000). It provides unweighted measurement on four domains: physical, psychological, social relationship and environment. The physical domain has questions related to daily activities, treatment compliance, pain and discomfort, sleep and rest, energy and fatigue. In the psychological domain, there are questions of positive and negative feelings, selfesteem, body image and physical appearance, personal beliefs and attention. The social relationship domain is related to personal relationships, social support and sexual activity. The environmental domain explores physical security and safety, financial resources, health and social care and their availability, opportunities for acquiring new information and skills, and participation in and opportunities for recreation and transport. WHOQOL-BREF-TR has acceptable psychometric properties in the Turkish population (Eser et al., 1999).

2.2.2 Assessment of cognitive functioning

Two neuropsychological tests assessing two maindomains of cognition were administered in the presentstudy; attention (Digit Span Test) and verbal fluency(Controlled Oral Word Association Test).

2.2.2.1 Digit Span Test. Digit Span Test (DST)

Digit Span Test. Digit Span Test (DST) in the Wechsler batteries is the format in most common use for measuring the span of immediate verbal recall (Wechsler, 1987; Lezak, 1995). This test has two sections, bDigits ForwardQ and bDigits BackwardQ which involve different mental activities and are differently affected by brain damage. Both of the tests involve auditory attention and both depend on a short-term retention capacity. In the bforwardQ section, the patient repeats the numbers told to him/her by the rater and in the bbackwardQ section, the patient repeats the numbers told to him/her backwards. The score is the sum of the correct recalled numbers in forwards and backwards sections and the total of the both sections as well. Performance on the backward digit span task is considered to measure working memory by requiring internal manipulation of mnemonic representations of verbal information in the absence of external cues (Conklin et al., 2000).

2.2.2.2 Controlled Oral Word Association Test.

The purpose of the test is to evaluate the spontaneous production of words beginning with a given letter or of a given class within a limited amount of time. F, A, S are the most commonly used letters for this test, as the letters. K, A, S were used in the Turkish reliability and validity study (Umac¸, 1997). Total score, the sum of all admissible words for the three letters, is used a measure in the present study. COWAT is also referred as a measure of executive functions assessing the ability to produce searching strategy to generate words and switch the cluster of the words (Spreen and Strauss, 1998).

2.2.3. Assessment of psychopathology and extrapyramidal side effects

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) (Kay et al., 1987; Kostakog˘lu et al., 1999) was used to obtain ratings for positive and negative symptoms. The extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic drugs were assessed by Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale (ESRS) (Chouinard et al., 1980).

2.3. Data analysis

The groups were compared with analysis of variance (ANOVA) for WHOQOL and cognitive test scores. Pearson correlation analyses were conducted to assess the relationship among measures of QoL, neurocognitive functioning and symptoms. Z-score was calculated for each neuropsychological test by using the means and standard deviations of control subjects. A summary score was generated by adding these Z-scores. The patient group was divided into two groups with neuropsychological test scoring below and above 1 S.D. of control subjects. These two groups were compared on quality of life domains with Mann Whitney U-test.

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of quality of life between patient and control groups

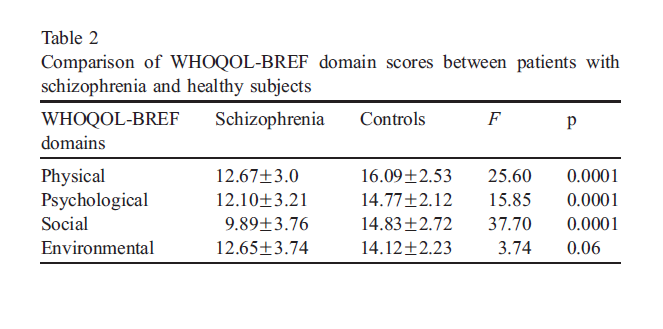

The patients with schizophrenia demonstrated lower scores in all domains whereas statistical significance was found in physical, psychological and social domains compared to control group (Table 2).

3.2. Comparison of cognitive functioning between patient and control groups

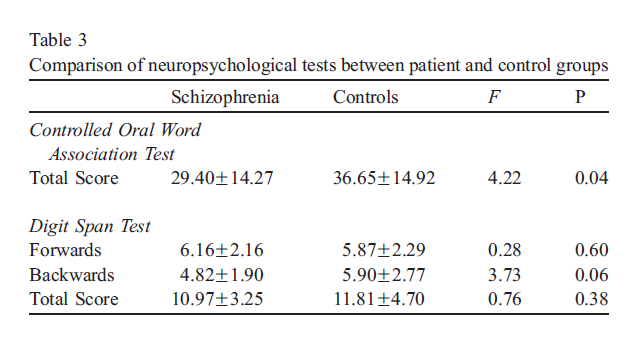

Two groups showed significant and nearly significant differences on scores of COWAT and DST, respectively. The patients with schizophrenia showed lower scores on COWAT and DST backwards section compared to healthy subjects (Table 3).

3.3. Relation of quality of life to cognition in patient and control groups

The social domain scores of WHOQOL were positively correlated to DST total (r=0.45, p=0.007) and DST forwards scores (r=0.54, p=0.001) in patients with schizophrenia. The social domain scores were also correlated to the total scores of COWAT (r=0.33, p=0.04) in the patient group. As the patients had higher social domain scores of WHOQOL, they had better performances for DST and COWAT. There was not any significant correlation between scores of quality of life and cognition in the control group.

3.4. Relation of quality of life to psychopathology and extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia

Positive and negative symptoms were not related to any domain of WHOQOL-BREF. ESRS scores were not correlated to either WHOQOL-BREF domains or cognitive tests.

3.5. Comparison of quality of life patients with different levels of cognitive impairment

The patient group showing cognitive scores at least 1 S.D. below controls showed lower scores on social domain compared to other patient group (z=-2.01, p=0.04). There were not any significant differences on the other three domains of QoL between these two groups.

4. Discussion

It has been clearly shown that individuals with schizophrenia have impaired neurocognitive functioning and reduced quality of life. However the relation of QoL to cognition has been somewhat unclear. The present study is noteworthy revealing significant association between some of the cognitive impairments (executive functions and working memory) and particularly social aspect of QoL in patients with schizophrenia.

4.1. Comparison of quality of life and cognition between patient and control groups

Our results are consistent with previous findings showing lower health related QoL scores of patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy subjects (Hermann et al., 2002). Schizophrenia is a chronic disorder that results in significant social, psychological and occupational dysfunction. People living with long-term psychosis report worse health related quality of life than the general population or patients with physical illness (Bobes and Gonzalez, 1997). Therefore, social integration, work, social contacts and acceptance into the environment must be the therapeutic goal to achieve a better quality of life. In the present study, the patients with schizophrenia showed lower scores in psychological, social and physical domains of quality of life. It is not surprising that we could not find a significant difference in environmental domain between two groups. Access to environmental resources, bstandard of living,Q is limited for the majority in our country as in other developing countries.

The patients showed lower scores on tests of verbal fluency and attention compared to healthy subjects. Verbal fluency and attention are mostly affected domains of cognition in schizophrenia (Kenny and Meltzer, 1991; Saykin et al., 1994; Mohamed et al., 1999). The backwards section of DST is considered to be a measure of working memory besides complex attention (Conklin et al., 2000), while COWAT is referred as a measure of executive functions as well as being a measure of verbal fluency (Spreen and Strauss, 1998). The results of the present study revealed that the patients with schizophrenia showed lower performance in working memory besides executive function compared to healthy subjects.

4.2. Relation of quality of life to cognition in patient and control groups

While the social domain was related to verbal fluency and attention in patients with schizophrenia, there was not any significant correlation between scores of quality of life and cognition in healthy subjects. Additionally, the patients with relatively lower (below 1 S.D.) scores of cognition had lower scores on social domain of QoL. These results support earlier researches that suggest an association between certain aspects of neurocognitive functioning and social functioning. Green et al. (2000) reported that outcome measures such as community functioning, social problem solving and psychosocial skill acquisition can be predicted by vigilance, working memory, verbal memory and executive functioning. Studies examining the predictive validity of neurocognition on QoL generally demonstrate weak to moderate correlations between different measures of neurocognition and QoL including verbal memory (Dickerson et al., 1998), vocabulary (Addington and Addington, 2000) and attention (Smith et al., 1999). Fujii et al. (2004) reported predictive value of various cognitive tests in several domains of QoL in a group of severe and persistent mental illness: predictive value of working memory in subjective satisfaction with social relations, executive functioning as a predictive of community functioning and ability to perform daily activities and memory with strong correlations to community functioning, social problem solving, as well as psychosocial skill acquisition. However, several studies examining the relationship between quality of life and neurocognitive deficits have reported weak associations (Heslegrave et al., 1997; Aksaray et al., 2002). The different sample sizes, lack of a control group in some of the studies, utilization of different tools for assessing QoL and cognition might explain the contradictory results among studies.

4.3. Relation of quality of life to psychopathology and extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic drugs in patients with schizophrenia

Although pyschopathology (Bow-Thomas et al., 1999; Ho et al., 1998) and extrapyramidal side effects (Voruganti et al., 2000; Aksaray et al., 2002) were reported to be related to QoL in patients with schizophrenia, they were not correlated to any domain of WHOQOL-BREF in the present study. Hansson et al. (1999) also reported that no clinical characteristics were correlated to QoL.

Cognitive deficits are important features of schizophrenia and might have a negative effect on the ability of schizophrenic patients to work and function in a social environment. Neurocognitive deficits restrict the functioning of patients with schizophrenia in the outside world. Therapeutic interventions that lead to cognitive improvement represent a major contribution in improving QoL among patients with schizophrenia. There is evidence that scores on neuropsychological assessments have improved after treatment with clozapine, risperidone and quetiapine (Schizophrenia Collaborative Working Group on Clinical Trial Evaluations, 1998). However, if functioning in social role is considered, the chances are less clear-cut that drugs might lead to quick improvement, and if social support and material living conditions are to improve again, it will probably take much longer and need other than psychopharmacological interventions (Katschnig and Krautgartner, 2002).

There are some limitations of the study. First, the validity of the patientsT self-reports is questionable; however, the subjective point of view is an inherent innovative aspect of QoL as it is conceptualized by the World Health Organization. It is concluded that clinically compliant and stable patients with schizophrenia can evaluate and report their quality of life with a high degree reliability and concurrent validity, implying that self-report measures are potentially useful tools in clinical trials and outcome studies (Voruganti et al., 2000). It is also reported that WHOQOL-BREF is sensitive to the health related QoL status of those with longterm mental illness (Hermann et al., 2002). As a second limitation, acutely psychotic patients were excluded. Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to all patient population. Another limitation of the study is the number of neuropsychological tests. The results of the neuropsychological tests measuring two major aspects of cognition cannot be interpreted as a generalized cognitive impairment.

5. Conclusions

Quality of life measures are especially important when treating patients with schizophrenia as they provide patients an opportunity to express what is and is not working in their lives. Our results confirm that the cognitive impairments in executive function and working memory appear to have direct impact on the patients’ perceived quality of life particularly in social domain which can either be a cause or a consequence of social isolation of patients with schizophrenia. The results of this study revealed that perceived quality of life was influenced by cognitive impairment but not by the severity of disease or drug side effects.

References

- Addington, J., Addington, D., 2000. Neurocognitive and social functioning in schizophrenia: a 2.5 year follow-up study. Schizophr. Res. 44, 47– 56.

- Aksaray, G., Oflu, S., Kaptanoglu, C., Bal, C., 2002. Neurocognitive deficits and quality of life in outpatients with schizophrenia. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 26, 1217–1219.

- American Psychiatric Association, 1994. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC.

- Bengtsson-Tops, A., Hansson, L., 1999. Subjective quality of life in schizophrenic patients living in the community: relationship to clinical and social characteristics. Eur. Psychiatry 14, 256– 263.

- Bobes, J., Gonzalez, M.P., 1997. Quality of life in schizophrenia. In: Katschnig, H., Freeman, H., Sartorius, N. (Eds.), Quality of Life in Mental Disorders. John Wiley and Sons, pp. 165–178.

- Bow-Thomas, C.C., Velligan, D.I., Miller, A.L., Olsen, J., 1999. Predicting quality of life from symptomatology in schizophrenia at exacerbation and stabilization. Psychiatry Res. 86, 131–142.

- Braff, D.L., Heaton, R., Kuck, J., Cullum, M., Moranville, J., Grant, I., Zisook, S., 1991. The generalized pattern of neuropsychological deficits in outpatients with chronic schizophrenia with heterogeneous Wisconsin Card Sorting Test results. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 48, 891– 898.

- Chouinard, G., Ross-Chouinard, A., Annable, L., 1980. Extrapyramidal symptom rating scale. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 7, 233.

- Conklin, H.M., Curtis, C.E., Katsanis, J., Iacono, W.G., 2000. Verbal working memory impairment in schizophrenia patients and their firstdegree relatives: evidence from the digit span task. Am. J. Psychiatry 157, 275– 277.

- Dickerson, F.B., Ringer, N.B., Parente, F., 1998. Subjective quality of life in out-patients with schizophrenia: clinical and utilization correlates. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 98, 124– 127.

- Eser, E., Fidaner, H., Fidaner, C., Eser, S.Y., Elbi, H., Gfker, E., 1999. Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-100 and WHOQOL-BREF. J. Psychiatry Psychol. Psychopharmacol. 7, 23–40 (in Turkish).

- Fujii, D.E.,Wylie, A.M., Nathan, J.H., 2004. Neurocognition and long-term prediction of quality of life in outpatients with severe and persistent mental illness. Schizophr. Res. 69, 67–73.

- Green, M.F., 1996. What are the functional consequences of neurocognitive deficits in schizophrenia? Am. J. Psychiatry 153, 321– 330.

- Green, M.F., Kern, R.S., Braff, D.L., Mintz, J., 2000. Neurocognitive deficits and functional outcome in schizophrenia: are we measuring the right stuff? Schizophr. Bull. 26, 119– 136.

- Hansson, L., Middelboe, T., Merinder, L., Bjarnason, O., Bengtsson-Tops, A., Nilsson, L., Sandlund, M., Sourander, A., Sorgaard, K.W., Vinding, H., 1999. Predictors of subjective quality of life in schizophrenic patients living in the community. A Nordic multicentre study. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 45, 247– 259.

- Hermann, H., Hawthorne, G., Thomas, R., 2002. Quality of life assessment in people living with psychosis. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 37, 510– 518.

- Heslegrave, R.J., Awad, A.G., Voruganti, L.N., 1997. The influence of neurocognitive deficits and symptoms on quality of life in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 22, 235– 243.

- Ho, B., Nopoulos, P., Flaum, M., Arndt, S., Andreasen, N.C., 1998. Twoyear outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: predictive value of symptoms for quality of life. Am. J. Psychiatry 155, 1196–1201.

- Katschnig, H., Krautgartner, M., 2002. Quality of Life: anew dimension in mental health care. In: Sartorius, N., Gaebel, W., Lopez-Ibor, J.J., Maj, M. (Eds.), Psychiatry in Society. John Wiley and Sons, pp. 171–191.

- Kay, S.R., Fiszbein, A., Opler, L.A., 1987. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr. Bull. 13, 261– 276.

- Kenny, J.T., Meltzer, H.Y., 1991. Attention and higher cortical functions in schizophrenia. J. Neuropsychiatry 3, 269– 275.

- Kostakog˘lu, A.E., Batur, S., Tiryaki, A., 1999. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). Turkish J. Psychol. 14, 23– 32.

- Lezak, M.D., 1995. Neuropsychological Assessment, 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 357– 360.

- Meltzer, H.Y., Thompson, P.A., Lee, M.A., Ranyan, R., 1996. Neuropsychological deficits in schizophrenia. Relation to social function and effect of antipsychotic drug treatment. Neuropsychopharmacology 14, 27S– 33S.

- Mohamed, S., Paulsen, J.S., O’Leary, D., Arndt, S., Andreasen, N., 1999. Generalized cognitive deficits in schizophrenia: a study of first-episode patients. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56, 749– 754.

- O’Carroll, R.E., Smith, K., Couston, M., Cossar, J.A., Hayes, P.C., 2000. A comparison of the WHOQOL-100 and the WHOQOL-BREF in detecting change in quality of life following liver transplantation. Qual. Life Res. 9, 121–124.

- Orley, J., Saxena, S., Herrman, H., 1998. Quality of life and mental illness. Br. J. Psychiatry 172, 291–293.

- Saleem, P., Olie, J.P., Loo, H., 2002. Social functioning and quality of life in the schizophrenic patient: advantages of amisulpride. Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 17, 1– 8..

- Saxena, S., Orley, J., 1997. Quality of life assessment: the World Health Organization perspective. Eur. Psychiatry 12, 263s– 266s.

- Saykin, A.J., Gur, R.C., Gur, R.E., Mozley, P.D., Mozley, L.H., Resnick, S.M., Kester, B., Stafiniak, P., 1991. Neuropsychological function in schizophrenia: selective impairment in memory and learning. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 48, 618–624.

- Saykin, A.J., Shtasel, D.L., Gur, R.E., Kester, D.B., Mozley, L.H., Stafiniak, P., Gur, R.C., 1994. Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first episode schizophrenia. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 51, 124–131.

- Schizophrenia Collaborative Working Group on Clinical Trial Evaluations, 1998. Measuring outcome in schizophrenia: differences among the atypical antipsychotics. J. Clin. Psychiatry 12, 3 – 9.

- Smith, T.E., Hull, J.W., Goodman, M., Hedayat-Harris, A., Willson, D.F., Israel, L.M., Munich, R.L., 1999. The relative influences of symptoms, insight, and neurocognition on social adjustment in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 187, 87–95.

- Spreen, O., Strauss, E., 1998. A Compendium of Neuropsychological Tests: Administration, Norms, and Commentary, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 447– 464.

- Umac¸, A., 1997. The influence of age and education to the tests sensitive to frontal lesions in normal subjects. Institute of Social Sciences at Istanbul University, Master Dissertation.

- Velligan, D.I., Miller, A.L., 1999. Cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia and its importance to outcome: the place of atypical antipsychotics in treatment. J. Clin. Psychiatry 60, 25– 28.

- Voruganti, L.N.P., Cortese, L., Oyewumi, L., Cernovsky, Z., Zirul, S., Awad, A., 2000. Comparative evaluation of conventional and novel antipsychotic drugs with reference to their subjective tolerability, side-effect profile and impact on quality of life. Schizophr. Res. 43, 135– 145.

- Wechsler, D., 1987. Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised. The Pychological Corporation, San Antonio, TX.

- WHOQOL Group, 1998a. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): development and general psychometric properties. Soc. Sci. Med. 46, 1569– 1585.

- WHOQOL Group, 1998b. The World Health Organization WHOQOLBREF quality of life assessment. Psychol. Med. 28, 551–558.