Clinical/Scientific Notes

Coexistence of Movement Disorders and Epilepsia Partialis Continua as the Initial Signs in Probable Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease

Berril Donmez, MD,1 Raif Çakmur, MD,1* Süleyman Men, MD,2 Ibrahim Oztura, MD,1 and Arzu Kitis, MD3

1Department of Neurology, Medical School of Dokuz Eylül University, Izmir, Turkey

2Department of Radiology, Medical School of Dokuz Eylül University, Izmir, Turkey

3Department of Psychiatry, Medical School of Dokuz Eylül University, Izmir, Turkey

Abstract: Movement disorders and epilepsy rarely occur in the early stage of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) but have not been reported concurrently. We report on a 47-year-old patient with probable CJD who presented with generalized chorea and focal dystonia with myoclonic jerks on the right hand. Myoclonic jerks progressed to epilepsia partialis continua within 5 days of admission to the hospital. The diagnosis of our patient was compatible with probable CJD on the basis of clinical course, electroencephalogram, and diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging findings, and presence of 14-3-3 protein in cerebrospinal fluid. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a case developing both movement disorders and epilepsia partialis continua in the early stage of the disease. © 2005 Movement Disorder Society

Key words: chorea; Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease; epilepsia partialis continua

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) is a rapidly progressive spongiform encephalopathy, which is usually fatal within a disease course of 1 year. Patients may present with nonspecific symptoms, rapid cognitive decline, or focal neurological signs such as ataxia, aphasia, visual loss, or hemiparesis.1,2 Various movement disorders, although very rare, have been reported as initial symptoms as well,1,3-5 whereas seizures mainly occur during the later disease stages. Two cases with CJD who have developed epilepsia partialis continua in the early stage of the disease have been reported

This article includes Supplementary Video, available online at www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/0885-3185/suppmat.

*Correspondence to: Dr.Raif Çakmur, Dokuz Eylül Universitesi, Tip Fakültesi, Noroloji Klinigi, Inciralti, Izmir 35340, Turkey.

E-mail: [email protected]

Received 9 July 2004; Revised 6 December 2004; Accepted 14 December 2004

Published online 13 May 2005 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/mds.20502

previously.6,7 We report on a 47-year-old woman with probable CJD who presented with generalized chorea and focal dystonia with myoclonic jerks on the right hand. Myoclonic jerks progressed to epilepsia partialis continua within 5 days of admission to the hospital. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a case developing both movement disorders and epilepsia partialis continua in the early stage of the disease.

Case Report

A 47-year-old woman presented with generalized chorea, dystonic posture, and myoclonic jerks on the right hand (see Video, Segment 1). She had a 3-week history of mild unsteadiness, concentration difficulties, and anxiety, moreover complained of numbness on the right hand for 2 weeks. In the initial neurological examination on admission, she was oriented to person, place, and time. The Mini-Mental State Examination score was normal; however, gait ataxia was noticed. Under low dose of haloperidol treatment (1.5 mg/day), choreic movements and dystonic posture diminished and myoclonic jerks progressed to epilepsia partialis continua within 5 days of admission to the hospital (see Video, Segment 2). Afterward, the haloperidol treatment was discontinued and anticonvulsive therapy (valproic acid 2,000 mg/day) was started, but her epilepsia partialis continua did not respond to treatment. Ten days after admission the patient developed lethargy, mild hemiparesis on the right, followed by cognitive decline. She became comatose 10 weeks after the disease onset and died 5 months later. Autopsy was not performed.

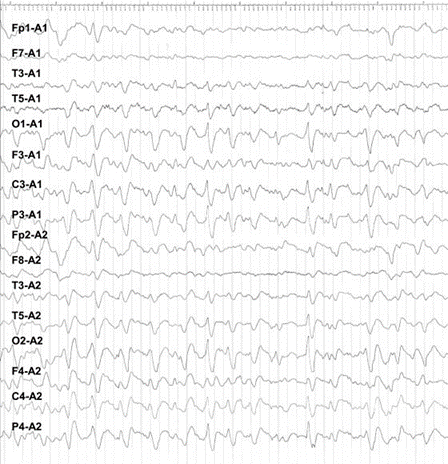

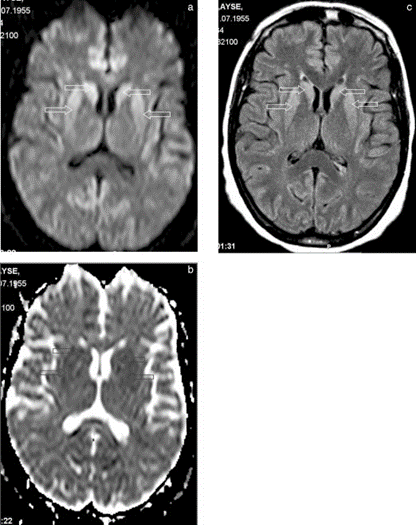

She had never received blood transfusions or growth hormone. She had no history of physical disease. By routine blood tests possible illnesses such as vasculitis, Wilson’s disease, neuroacanthocytosis, dysfunction of the thyroid gland, vitamin B12, and folate deficiencies, hepatitis B, syphilis, brucellosis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) could be excluded. Chest X-ray and abdominal ultrasonogram were normal. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination was performed twice, showing normal values as for the standard parameters. However, the 14-3-3 protein was found supporting the diagnosis of CJD. An initial electroencephalogram (EEG) demonstrated diffuse slowness of basal rhythm marked on left side and biphasic sharp waves correlating with myoclonic jerks. During follow-up, 3 weeks after admission, typical triphasic sharp waves occurred (Fig. 1). The initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans (T1, T2, and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery [FLAIR]) were assessed as normal. However, 3 weeks later, signal increase of the basal ganglia was found, most remarkable on diffusion-weighted images (DWI; Fig. 2a- c).

Discussion

Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease is a rare transmissible neurological disorder clinically characterized by rapidly progressive dementia, myoclonus, ataxia, and extrapyramidal symptoms.1 Although the diagnosis of definite CJD can only be made by histopathological investigation, probable CJD is defined as

FIG. 1. Triphasic sharp waves, superimposed on a depressed background.

progressive dementia with at least two of the following: myoclonus, visual or cerebellar signs, pyramidal or extrapyramidal signs, akinetic mutism.8 Moreover, the diagnosis of probable CJD requires sharp and slow wave complexes in EEG and/or the findings of 14-3-3 protein in the CSF. Our patient fulfilled the criteria of probable CJD on the basis of clinical course, EEG findings, and the presence of 14-3-3 protein in CSF. Alternative diagnoses at the onset of the disease were all excluded with appropriate laboratory tests. Our case is noteworthy as it shows how difficult it might be to diagnose CJD with atypical clinical onset.

Movement disorders typically appear during the later disease stages but rarely as an initial symptom of CJD. A study investigating clinical features of 230 CJD patients has reported only 1 patient who complained of choreoathetotic movements at the onset of illness.1 In another study, dyskinesia at the disease onset could be found in 4 of 300 CJD cases.9 Moreover, a patient presenting with ataxia and dystonia and another patient showing focal dystonia at the beginning have been reported.3,4 A case of variant CJD (nvCJD) developing chorea in the early stages of the disease has been reported as well.10

Rasmussen’s syndrome, HIV infection, cerebrovascular pathological state, or brain tumors can lead to epilepsia partialis continua.11,13 Only two cases of CJD have been reported who have developed epilepsia partialis continua as the first sign of the disease.6,7

The 14-3-3 brain protein has been demonstrated to be positive in 93% of patients with CJD as well as in our case. With a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 84%, the detection of the 14-3-3 protein in the CSF has been proven to be a good diagnostic marker for CJD, exceeding the sensitivity of EEG.8 As a marker of massive neuronal loss, the 14-3-3 protein can also be found after stroke, encephalitis, and after epileptic seizures. Thus, in our case, the finding of the 14-3-3 protein could have also been due to epilepsia partialis continua, and additional clinical symptoms and diagnostic findings (MRI) were required to support the diagnosis of CJD.

Bahn and colleagues14 were the first investigators to demonstrate a bilateral symmetrical marked increase in signal intensities of caudate nucleus, putamen, thalamus, and cingulate gyrus on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance images, which might be sensitive for CJD. In a recent study examining 26 probable CJD cases, a sensitivity of 92% was found for signal increase of the basal ganglia or cortex on DWI.15 Diffusion abnormalities in basal ganglia on MRI were also found in our case, supporting the diagnosis of CJD.

To our knowledge, this is the first case report of coexistence of movement disorders and epilepsia partialis continua as the initial

FIG. 2. a: Axial diffusion-weighted image through basal ganglia. Note increased intensity in caudate nuclei and putamina (arrows). b: Apparent diffusion coefficient map (B = 1,000 s/cm2) confirms restricted diffusion in the corresponding areas (arrows). c: Abnormal signal intensity is appreciated also in fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images (arrows).

signs in probable CJD. Our case indicates that chorea, dystonia, and epilepsia partialis continua may occur in the early stage of the disease and should be considered in the diagnosis of CJD.

Legends to the Video

Segment 1. The patient has generalized involuntary choreic movements prominent on the right side while sitting and lying down. While walking, she has walking ataxia and dystonia on the right hand.

Segment 2. The patient has epilepsia partialis continua in the right hand.

References

- Brown P, Cathala F, Castaigne P, Gajdusek DJ. Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease: clinical analysis of a consecutive series of 230 neuropathologically verified cases. Ann Neurol 1986;20:597- 602.

- Johnson RT, Gibbs CJ. Medical progress: Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease and related transmissible spongiform encephalopathies. N Engl J Med 1998;339:1994 -2004.

- Sethi KD, Hess DC. Creutzfeldt-Jakob's disease presenting with ataxia and a movement disorder. Mov Disord 1991;6:157-162.

- Hellmann MA, Melamed E. Focal dystonia as the presenting sign in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Mov Disord 2002;17:1097-1098.

- Will RG, Matthews WB. A retrospective study of Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease in England and Wales: 1970 -79. I. Clinical features. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1984;47:134 -140.

- Lee K, Haight E, Olejniczak P. Epilepsia partialis continua in Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease. Acta Neurol Scand 2000;102:398 - 402.

- Parry J, Tuch P, Knezevic W, Fabian V. Creutzfeldt-Jakob syndrome presenting as epilepsia partialis continua. J Clin Neurosci 2001;8:266 -268.

- Zerr I, Pocchiari M, Collins S, et al. Analysis of EEG and CSF 14-3-3 proteins as aids to the diagnosis of Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease. Neurology 2000;55:811- 815.

- Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, et al. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol 1999;46:224 -233.

- Bowen J, Mitchell T, Pearce R, Quinn N. Chorea in new variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Mov Disord 2000;15:1284 -1285.

- Bartolomei F, Gavaret M, Dhiver C, et al. Isolated, chronic, epilepsia partialis continua in an HIV-infected patient. Arch Neurol 1999;56:111-114.

- Cockerell OC, Rothwell J, Thompson PD, Marsden CD, Shorvon SD. Clinical and physiological features of epilepsia partialis continua: cases ascertained in the UK. Brain 1996;119:393- 407.

- Juul-Jensen P, Deny-Brown D. Epilepsia partialis continua. Arch Neurol 1996;15:563-578.

- Bahn MM, Kido DK, Lin W, Pearlman AL. Brain magnetic resonance diffusion abnormalities in Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Arch Neurol 1997; 54:1411-1115.

- Shiga Y, Miyazawa K, Sato S, et al. Diffusion-weighted MRI abnormalities as an early diagnostic marker for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology 2004;63:443- 449.

Stages 1-2 Non-Rapid Eye Movement Sleep Behavior Disorder Associated With Dementia: A New Parasomnia?

Isabelle Arnulf, MD, PhD,1* Tarek Mabrouk, MD,2 Khalil Mohamed, MD,2 Eric Konofal, MD,PhD,1 Jean-Philippe Derenne, MD,1 and Philippe Couratier, MD, PhD2

1Fe´de´ration des Pathologies du Sommeil, Groupe Hospitalier Pitie´-Salpeˆtrie`re, Assistance Publique-Hoˆpitaux de Paris, Paris, France

2Neurologie B, Centre Hospitalo-Universitaire Dupuytren Limoges, France

Abstract: A 55-year-old woman with a progressive dementia and frontal syndrome was hospitalized because she was agitated every night after falling asleep (spoke, laughed, cried, tapped, kicked, walked, and fell down). She slept 5.5 hours during video polysomnography, but the theta rhythm electroencephalograph recording typical of sleep stages 1 to 2 and the spindles and K-complexes typical of sleep stage 2 contrasted with continuous muscular twitching, prominent rapid eye movements, vocalizations, and continuous, complex, purposeful movements typical of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder. This newly described stages 1-2 non-REM sleep behavior disorder suggests that central motor pattern generators were disinhibited during non-REM sleep. © 2005 Movement Disorder Society

This article includes Supplementary Video, available online at www.interscience.wiley.com/jpages/0885-3185/suppmat.

*Correspondence to: Dr. Isabelle Arnulf, Fe´de´ration des Pathologies du Sommeil, Hoˆpital Pitie´-Salpeˆtrie`re, 47- 83 Boulevard de l’Hoˆpital, 75651 Paris Cedex, France. E-mail: [email protected] Received 9 August 2004; Revised 29 December 2004; Accepted 29 December 2004

Published online 17 June 2005 in Wiley InterScience ( www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/mds.20517

Key words: parasomnia; REM sleep behavior disorder; non-REM sleep; status dissociatus; dementia

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is characterized by abnormal behaviors emerging during REM sleep that cause injury or sleep disruption. RBD is also associated with loss of normal REM sleep atonia.1 This parasomnia is frequently observed in patients with neurodegenerative dementia, mainly synucleinopathies.2,3 Here, we describe a patient with a progressive dementia who suffered from abnormal and violent sleep-associated behaviors, emerging during both REM and non-REM sleep and lasting as long as sleep lasted.

Case Report

Ms. C. was a 55-year-old mother of five children, working as a maid. She had no clinically significant medical history; no past personal or familial history of dementia, sleepwalking, or sleep terrors; and had presented a unique episode of mild depression 3 years ago. Her husband died in May 2003, and she developed a progressive mild cognitive impairment, altered time and space orientation, and a mild apathy refractory to antidepressant treatment. In September 2003, her daughters complained of her abnormal behaviors exclusively restricted to nighttime. After falling asleep, she sat on her bed, with eyes closed, gesticulated (“picking up beans”, they said), and spoke to her dead husband or her absent grandson. One night she screamed and ran in the house, becoming quiet when her daughter “woke” her; she reported having a terrible nightmare with people trying to kill her children. She was also found turning around the table without seeing her daughter. She knocked over her bedside table and turned her linen closet upside-down. During the daytime, the patient, in contrast, was quiet, able to write, read, cook, and answer casual questions. In November 2003, she had her first neuropsychological tests. The copy she made of the Rey–Osterrieth Complex Figure4 contained juxtaposed details but was coherent. Constructional praxis of the Luria Graphic Sequences were adequately reproduced.5 Spontaneous writing was correct, whereas writing under dictation contained orthographic errors that were considered to be linked to her poor academic level. Reading was correct, but copying of read sentences revealed omissions caused by attention deficiency. Reflexive praxis was good, whereas reproduction of gestural sequences of Luria (such as the fist-edge-palm test) were moderately impaired. During the test of image denomination, her speech contained multiple semantic paraphasic errors and shortage of words caused by verbal memory deficiency. She scored 13/28 (for a standard note of 8) on the similarities subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-revised6 and 3/6 on the clinical subtest of the Wechsler Memory Test-revised.7 She was able to count backward from 20 to 1, and to count by threes, but forgot the instructions during the test. During the test of numbers series recall, she scored 5/12 in direct order and 3/12 in reverse order (total 8/24), confirming important memory disturbances. She scored 12/14 on the time and space orientation tests: she was able to give her age, her date of birth, the day of the week (but not the date), the clock time, the month and year, and the place where she was, but named a former president than the actual one. She had a mild euphoric mood and anosognosia.

Because she was walking nightly in the house, sometimes falling down (but rarely hurting herself) and staying lying on.

Movement Disorders, Vol. 20, No. 9, 2005